Colonial Period: 1600s-1700s — Essential Craft in Early Settlements

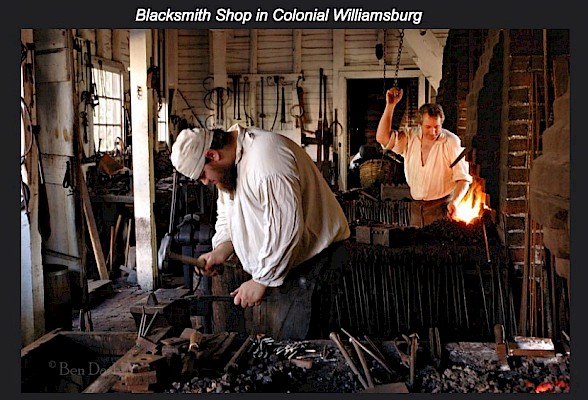

Blacksmithing in what became the U.S. began with the earliest English colonies. A blacksmith accompanied the Jamestown settlement in 1607, and soon became one of the most important trades in any new community. Blacksmiths forged essential tools, hardware, nails, horseshoes, wagons parts, and weapons needed for farms, homes, frontier life, and defense. They served as jacks-of-all-trades because imported goods were scarce and difficult to replace on the frontier.

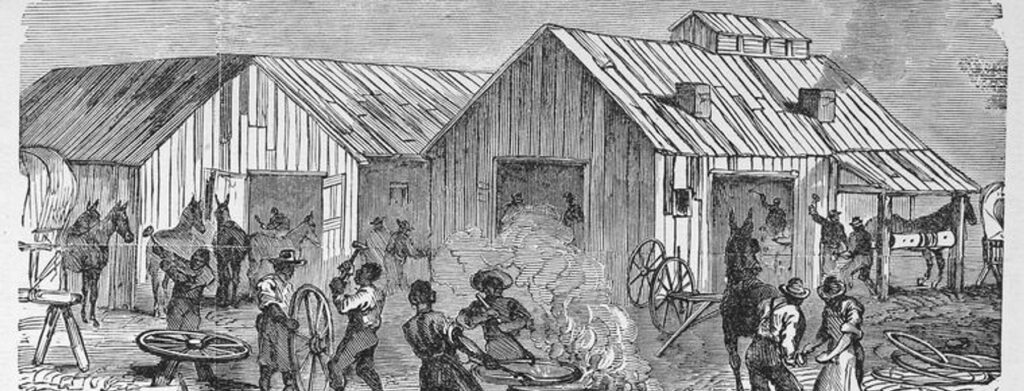

Blacksmiths worked not only as independent craftsmen but also trained apprentices or enslaved workers, and in places like Colonial Virginia enslaved blacksmiths were widely employed and contributed significantly to production.

During the American Revolution, blacksmiths were even attached to military units, making and repairing metal parts and equipment on the move.

Early Republic to Mid-19th Century — Growth with Expansion

By the early 1800s, blacksmith shops were ubiquitous across the young United States, especially as settlers pushed westward. They were vital to rural and urban communities alike, producing tools, wagon parts, farm implements, and hardware. By about 1810, Pennsylvania alone reported thousands of blacksmith shops with significant economic output.

Economic historians note that blacksmiths were widespread through the first half of the 19th century. In 1850 there were hundreds of thousands of smiths and related craftsmen making everything from tools to carriage parts.

A notable figure from this era was Cornelius Atherton, a blacksmith who helped pioneer steel production in Colonial America and supplied cutlery and firearm parts during the Revolution.

Late 19th Century — Industrialization and Change

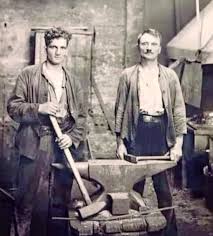

As the United States industrialized, mass production of metal goods expanded rapidly. Factories could make nails, tools, horseshoes, and hardware more cheaply and in greater volume than individual smiths. With railroads and industrial manufacturing, the traditional blacksmith’s role began to shift from essential producer to service and repair specialist in many regions.

By the end of the 19th century, many smith shops were adapting — some focusing on specialized work (like wagon and carriage fitting), ornamental ironwork, or farriery (horseshoeing). Historic examples of long-operating shops from this era include G. Krug & Son Ironworks, founded in 1810 and still active today as one of the oldest blacksmith businesses in the U.S.

Early 20th Century — Decline as Necessity Shrinks

With the rise of automobiles and machine tools in the early 20th century, demand for traditional blacksmith services like wagon repair or horseshoeing declined sharply. Many smiths either became general repair mechanics or went out of business altogether. By the 1920s and 1930s, blacksmithing in its traditional form was much less common.

Historic blacksmith shops from this time, such as the Quasdorf Blacksmith and Wagon Shop (built 1899, used into the 1990s), survive today as museums preserving that legacy.

Late 20th Century to Present — Revival, Craft, and Art

Late 20th Century to Present — Revival, Craft, and Art

In the late 20th century, especially around the U.S. Bicentennial (1976) and afterward, there was a resurgence of interest in traditional crafts and heritage skills. This sparked renewed interest in blacksmithing — not so much as a necessity but as artisanal craft, heritage demonstration, and hobbyist pursuit.

Today, blacksmithing in the U.S. is practiced by artisans, hobbyists, historic interpreters, and specialized craftsmen. Organizations and events (like hammer-ins and living history demonstrations), and historic forges and museums (such as those at Boomtown museums) sustain and teach the trade to new generations.